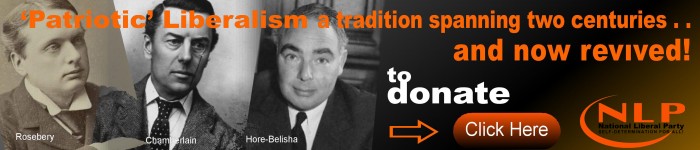

Historical Figures

This is a new section which we have introduced looking at some of our forebears who have combined a healthy nationalism with their liberalism.

We would like to research the works and lives of leading personalities of the UK’s Liberal Nationals (1930-48) and similar historical and contemporary figures in other countries in more detail by setting up a political Foundation dedicated to researching and promoting the tenets of National Liberalism. We are seeking a serious sponsor(s) for this work which will be launched within two years. Details and funding are open to negotiation. Can you help? If you are interested in promoting an alternative liberalism then contact natliberal@aol.org

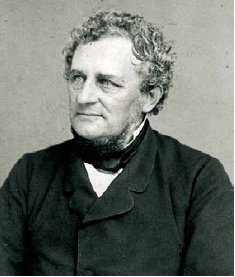

Giuseppe Mazzini (1805-1872)

Mazzini was a 19th century Italian dissident who united the two developing schools of radical political thought of the time: Nationalism & Liberalism. Liberals opposed the dynastic, largely anti-democratic governments, prevalent in Europe. They came to see that national sentiment could unite the ordinary person and would be endorsed by democratic mechanisms i.e. elections, referenda etc. Nationalists were happy to see the Monarchs go as they were, aside from Empires, the main obstacles to nation-states and thus embraced democracy as the way forward. Some, like Mazzini, argued for both i.e. liberation of the people (via democracy) and of the public (via a nation-state).

Mazzini was a 19th century Italian dissident who united the two developing schools of radical political thought of the time: Nationalism & Liberalism. Liberals opposed the dynastic, largely anti-democratic governments, prevalent in Europe. They came to see that national sentiment could unite the ordinary person and would be endorsed by democratic mechanisms i.e. elections, referenda etc. Nationalists were happy to see the Monarchs go as they were, aside from Empires, the main obstacles to nation-states and thus embraced democracy as the way forward. Some, like Mazzini, argued for both i.e. liberation of the people (via democracy) and of the public (via a nation-state).

Born in Genoa in 1805 he spent a lifetime of political agitation and exile (founding in London in 1858 a newspaper ‘Pensiero e azione (“Thought and Action”)). Although an Italian Nationalist he fostered similar thought throughout Europe i.e. forming a Young Poland and Young Switzerland etc modeled off his Young Italy organization. His preferred methods were revolutionary but ultimately it was the work of another Nationalist (Garibaldi) who, by accepting the ‘leadership’ of another state Piedmont, turned the dream into a reality. Fortunately he did live to see the final act in Italian Unification i.e. the Liberation of Rome before dieing in 1872.

Mazzini’s polemics inspired many Italian patriots including Garibaldi. Sadly, whilst ‘National Liberalism’ took solid root after the mid-nineteenth century, anti-democratic tendencies began to take hold within nationalist thought (such as the Bonapartists in the Third French Republic) and anti-national feeling within Liberal thought by the onset of the 20th century.

Given the present threat to the nation-state from internationalist quangos and political bodies such as the EU and the threat to civil liberties within modern Western states it is time for Nationalism/patriotism and Liberalism to once again work hand in hand.

Benningson (1824-1902)

Rudolf Benningson was a 19th century Hanoverian politician. Although he became a recognised liberal opponent of a reactionary Hanoverian monarchy he was better known throughout the whole of Germany (then dis-united) as the founder of the Nationalist Association.

This aimed to create a national party striving for unity and the consitutional liberty of the whole of Germany. It united moderate Liberals throughout Germany since it embraced a growing sentiment whilst resisting any loss of liberties i.e. to a ‘strong man’.

He became President of a new National Liberal Party in 1867. Whilst happy to see Germany expand by uniting with smaller states he was instrumental in building Parliamentary institutions which helped keep in check any abuse of power by Germany’s contemporary ‘strong man’.

After Benningson’s resignation from Parliament in 1883 in opposition to Bismark’s reactionary policies his influence declined. Without his guiding hand the National Liberals increasingly fell under the influence of big business. Under threat from the new Socialists on the left it gradually became more conservative, although it was generally divided between a more liberal wing that sought to strengthen ties with the dissident liberals to their left, and a right wing that came to support more protectionist policies and closer relations with the Conservatives and the Imperial Government. Ultimately this led to a major split upon the conclusion of the First World War.

Benningson was a patriotic liberal, passionate about the unity of Germany yet a strong believer in individual liberties and constitutional reforms. His major role, which was laregly succesful for thirty years, was in keeping the ‘authoritarian impulses’ of some nationalists (not least Bismark) in check.

Lasker (1829-1884)

Eduard Lasker was a founding member of the German National Liberal Party and the architect of the great judicial reforms of 1867-1877 which sought to intoduce a unified law(s) whilst preserving indidual liberties. His forte was in finding compromises between a Government looking to restrict liberties in the interests of ‘effeciency’ and Radicals who wished to oppose the existing order regardless.

Born of a Jewish tradesman in Silesia he typified the strong patriotic tradition, particularly articulated by the Rabbi Raphael Hirsch, held by many German Jews right up to First World War.

In common with all German National Liberal politicians in the 1880’s onwards he suffered from political swings to left and right. Once German Unity had been achieved and liberties enshrined in law (albeit limited) interest began to focus on Imperial expansion and worker emancipation. Conservatives and Socialists were thought to best represent those goals and the voters began to desert the NLP up to the First World War and their ultimate demise.

Lasker epitomised the fusion of a belief in individual liberty within the framework of a great nation-state and since the desire for greater liberty and national unity was uppermost in German Society in the mid-nineteenth century it is not surprising that the NLP dominated German politics between 1870-1880.

Sir John Simon (1873-1954)

Sir John Simon, a lawyer, was originally elected to Parliament as a Liberal in 1906. He remained an MP on and off until winning the seat of Spen Valley in 1922 which remained his ‘stronghold’ until taking a peerage in 1940.

Sir John Simon, a lawyer, was originally elected to Parliament as a Liberal in 1906. He remained an MP on and off until winning the seat of Spen Valley in 1922 which remained his ‘stronghold’ until taking a peerage in 1940.

Simon was one of a group of Liberals who disliked the party policy of keeping a minority Labour Government in power from 1929. They also supported the introduction of tariffs as a way of protecting British industry from the affects of the depression then damaging the world’s economies and this further fuelled int ernal conflict. In 1931 these Liberals coalesced around Simon who supported the new National Government (a cross-party coalition). The division soon became a permanent schism that lasted up and until the conclusion of the Second World War.

In May 1947 after the massive swing to Labour after the end of the War an agreement to merge the Conservative and the Liberal Nationals at constituency level (‘Woolton-Teviot’) at which the latter renamed themselves as the National Liberals. Unfortunately this ultimately became more a flag of convenience for the ‘merged’ groups to appeal to the Liberal voter rather than a separate party. Sir John was not destined to witness this ignominy as he died in 1954.

Whilst the party ran into sand there had been an opportunity for the Liberal Nationals to become the premier Liberal organisation in the late thirties and even after the war (they had more MPs than the Liberal Party in the 1950’s). Although this was not to be, Simon had at least led a Liberal group that had highlighted the inherent differences within liberalism and one which had put country before party and the worker before dogma. With your help we hope to continue and develop the ‘national’ tradition.

Orla Lehmann (1810-1870)

Orla Lehmann (1810-1870) was a Danish politician and a leading member of the Danish National Liberal Party (one of the earli est in Europe, around 1830+, and possibly the first to use the name. They were also known as the intellectuals’ party as many belonged to the educated middle class).

est in Europe, around 1830+, and possibly the first to use the name. They were also known as the intellectuals’ party as many belonged to the educated middle class).

His involvement with the party began at an early stage writing for liberal newspaper (Copenhagen Post) before becoming an editor of the National Liberal supporting magazine ‘The Fatherland’. Whilst his initial passion was in liberalising the Danish political system by replacing absolute monarchy with a democratic constitution he later added on a patriotic desire to unite with fellow countrymen in Schleswig (“Denmark to the Eider!” was an NLP slogan).

Orla Lehmann formulated the Ejder program in 1842 . The Eider program (the River Eider being the desired southern border) aimed to absorb the Schleswig province into Denmark whilst, unlike Conservatives, releasing the German Duchies of Holstein and Lauenburg (presently under the Danish Monarchy). Denmark Thus many Liberals, heavily influenced by national romantic/cultural ideals, became National Liberals.

In 1848 Europe erupted in Liberal, Nationalist and National Liberal revolutions. In Denmark the desire for change was driven by the latter. In March mass rallies, one of which Lehmann addressed, called upon the King to accept a new democratic and national system of government. Under this pressure and the fear of revolution the King appointed a Constitutional Ministry composed of National Liberals and Conservatives.

Ultimately, whilst the first Schleswig war (1848-51) with Germany helped unite the country the second (1864) led to the loss of the province (and 200,000 citizens) and the slow demise of the party.

Although Lehmann was later eclipsed by younger NL leaders e.g. Christian Hall who implemented many of their original democratic demands in the late 1850’s he was held in high esteem by his countrymen as an inspirational figurehead who had broken the power of monarchy. For us he will be remembered as someone who could combine a passion for both his country and people and where democracy and patriotism are two sides of a coin.

Earnest Brown (1881-1962)

Earnest Brown (1881-1962). Was a British MP and leader of the Liberal National Party from 1940-1945. Although English he primarily represented the Edinburgh constituency seat of Leith for nearly 20 years. Like many other Liberal MPs he became disillusioned with the Party’s leadership over its refusal to consider import tariffs and became with (Sir) John Simon a founding member of the new Liberal National Party in 1931.

Earnest Brown (1881-1962). Was a British MP and leader of the Liberal National Party from 1940-1945. Although English he primarily represented the Edinburgh constituency seat of Leith for nearly 20 years. Like many other Liberal MPs he became disillusioned with the Party’s leadership over its refusal to consider import tariffs and became with (Sir) John Simon a founding member of the new Liberal National Party in 1931.

As a valued member of the National Coalition of the time (including Labour, Liberal and Conservative MPs) he held Ministerial rank continuously until losing his seat in the ‘Labour landslide’ in 1945. His most memorable position was Minister of Labour. He oversaw legislation which extended social security to nearly all agricultural workers and supported the right of Trade Unionists to actively recruit.

After John Simon was appointed to the Lords Earnest Brown took over leadership of the LN’s in 1940. He attempted to unite the two divided Liberal parties but talks foundered over continuing support for a National Coalition.

Sadly he was unable to breathe life into the party who suffered losses in the swing towards Labour whilst relying upon the mercy of their Conservative ‘partners’. Brown himself lost his seat in ‘War’ election in 1945 and dropped out of politics.

Although he did not have the status of Simon or the ‘vision’ of Henderson-Stewart he was a social reformer in a cabinet of conservatives (with a little and large C). He also believed that the LNs were the more legitimate heirs to the Liberal tradition (rather than the Independent Liberals) because they put individual liberty at the forefront of their beliefs.

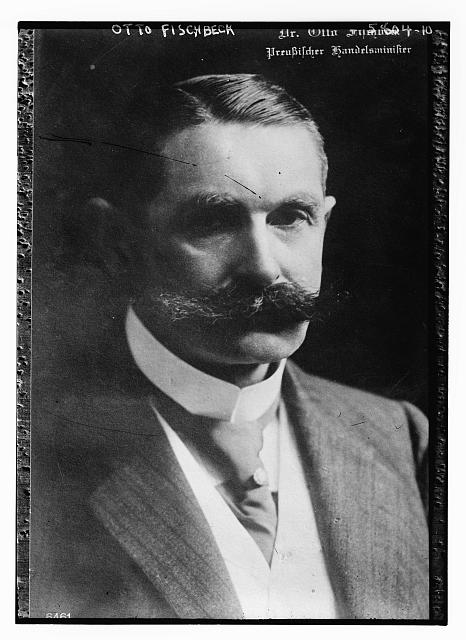

Otto Fischbeck (1865-1939)

Was a German politician between the turn of the 19th century until 1930. He was an MP first for the Liberal People’s Party before it amalgamated with a number of left-leaning Liberal Parties (in comparison to the, by that time, right-leaning National Liberal Party) as the Progressive People’s Party. Thereafter he was its’ Parliamentary leader for two years and Lower Silesian Chairman until its’ dissolution after the First World War.

an MP first for the Liberal People’s Party before it amalgamated with a number of left-leaning Liberal Parties (in comparison to the, by that time, right-leaning National Liberal Party) as the Progressive People’s Party. Thereafter he was its’ Parliamentary leader for two years and Lower Silesian Chairman until its’ dissolution after the First World War.

In 1918 he was instrumental in calling for a union of all liberal forces in Germany including Gustav Stresseman of the NLP (Unfortunately while the more left-wing elements accepted ex-members of the NLP their objection to Stresemann’s support for the annexation of territory if German won the war (even though Fischbeck had too!) blocked his membership. Thus Stresemann went onto form a rival German People’s Party which, although ultimately more right-wing, under his leadership was a pragmatic ‘National Liberal’ force i.e. democratic reform at home whilst fighting against an iniquitous Versailles Treaty abroad).

Fischbeck kept with the newly formed German Democratic Party (DDP), becoming a Regional MP and sometime Minister in Prussia and finally an MP in the National Parliament before the party merged in 1930 (into the German State Party) in an unsuccessful attempt to arrest its’ decline.

Unlike the majority of his DDP colleagues he still regarded himself as nationalist or ‘Volkisch Liberal’ rather than a ‘Universalist’ (Although many ‘Volkish Liberals’ were infected by a poisonous anti-semitism Fischbeck claimed that he wasn’t and only objected to those, including Jews, who claimed special rights in the party due to their financial contributions i.e. a contemporary form of ‘positive discrimination’. Thus perhaps a cultural rather than ethno-nationalist?). Whatever his flaws he was a lifelong Liberal Nationalist whose voice was ultimately drowned out by the louder extremes of far left or right.

Hoare-Belisha (1893–1957)

Leslie Hoare-Belisha is remembered as the man who introduced pedestrian crossing markers known as ‘Belisha Beacons’. He was also a leading member and founder of the Liberal National Party (1931).

To combat the effects of the Great Depression he and a number of other Liberal  MPs believed that the imposition of tariffs was the only way that British industry could be protected from ‘export dumping’ from abroad. Only when everyone was protected could tariffs be removed through negotiation for mutual benefit (similar to Nuclear ‘downsizing’). The price to pay for following that policy was a split in the Liberal Party between Liberals and Liberal Nationals.

MPs believed that the imposition of tariffs was the only way that British industry could be protected from ‘export dumping’ from abroad. Only when everyone was protected could tariffs be removed through negotiation for mutual benefit (similar to Nuclear ‘downsizing’). The price to pay for following that policy was a split in the Liberal Party between Liberals and Liberal Nationals.

An ambitious man and a brilliant speaker he was quickly elevated to a Ministerial career in a ‘National (cross-party) Government’ starting in the Treasury, excelling as Transport Minister but failing ignominiously as Secretary State for War.

Liberal National politicians largely split into two types; those who stayed in their ranks for personal and practical reasons and those who believed they represented an alternative Liberal tradition* to that which they had left behind in the Liberal Party. Prior to 1940 Hoare-Belisha fell into the latter group. He was active in trying to develop the party structure, a prolific writer and was eager to carve out an independent role for the LN’s. He said ‘We shall have to fight and I think take the offensive for the soul of Liberalism, maintaining we are in the Rosebery tradition.’ This was roughly translated as – the national interest first when abroad and social reform first when at home. Sacrificing a modicum (or so they thought!) of independence by being in a National Government (which included Labour and (mainly) Conservatives) was also seen as ‘putting the Country first.’

Like many LN members however there was always a dynamic tension between being in partnership yet maintaining their independence. Some feared being swallowed up by their Conservative partners (as occurred to the Liberal Unionists decades earlier) and ultimately drifted back to the Liberals whilst others succumbed to absorption. Hoare-Belisha had fought to maintain the LN’s independence but he reacted badly to his sacking as Secretary of War in 1940 amidst accusations (and counter) of anti-semitism and war mongering. He never forgave his LN Ministerial colleagues for their resultant lukewarm support in Cabinet.

He subsequently became an (National) Independent MP but lost his seat in the Labour landslide in 1945. He later drifted into the Conservative party. A sad end to a promising career.

Of course with courage and luck the LN’s might have carved out an independent future (from the Conservatives and (social) Liberals) and continued as an important political force. Hoare-Belisha is likely to have remained one of them.

* Other articles on the site explore this tradition.

GUSTAV STRESEMANN (1878-1929)

Gustav Stresemann was a post-WW1 German Chancellor and Foreign Minister. As a young student he was drawn to a Liberal movement attempting to limit the power of the German Emperor Wilhelm II over Parliament (Reichstag). He combined his liberalism with a strident nationalism and whilst initially attracted to the ideas of the Liberal reformer (and nationalist) Friedrich Naumannn he ultimately threw his lot in with the National Liberals.

The latter was more a coalition than a single-minded party, one wing (that Stresemann was part of) focused on social reform while still ‘patriotic’ in foreign policy whilst the other had moved towards supporting business as part of a ‘nationalist’ agenda. Despite the differences Stresemann’s natural charisma and organisational skills attracted support from all wings of the party and, under the ‘unifying stresses’ of the First World War, took over leadership of the party (which had lost a lot of support since its’ heyday in the 1870’s).

The end of the War led to the abdication of the Emperor, the creation of the Wiemar Republic and a host of new parties. Stresemann initially joined the newly formed German Democratic Party (DDP) in 1918 but was rejected given his previous ‘annexationist’ views and formed the German People’s Party (DVP) the following year. The party promoted Christian family values, secular education, lower tariffs, opposition to welfare spending and agrarian subsides. Some of these policies could be seen in line with his earlier (reformist) National Liberal agenda but reducing welfare spending not. It seems however Stresemann was trying to find the cuts needed to pay the debt dictated by Versailles. Failure to do so would invite invasion and a loss of self-governance. He was protecting Germany’s status as a nation state. Internally he called for an end to the restrictive Prussian franchise and supported pure representative democracy.

Wiemar Republic and a host of new parties. Stresemann initially joined the newly formed German Democratic Party (DDP) in 1918 but was rejected given his previous ‘annexationist’ views and formed the German People’s Party (DVP) the following year. The party promoted Christian family values, secular education, lower tariffs, opposition to welfare spending and agrarian subsides. Some of these policies could be seen in line with his earlier (reformist) National Liberal agenda but reducing welfare spending not. It seems however Stresemann was trying to find the cuts needed to pay the debt dictated by Versailles. Failure to do so would invite invasion and a loss of self-governance. He was protecting Germany’s status as a nation state. Internally he called for an end to the restrictive Prussian franchise and supported pure representative democracy.

Although initially sceptical of the new Republic, out of all the German politicians he was one who really wanted to make Germany’s post-war democracy work and create a stable state. From the 1920s onwards Stresemann became an ever more powerful figure. Eventually he became the Chancellor and introduced initiatives to ease relationships with the other European powers and improve the economy.

Even after the coalition government fell apart a new one was formed with him as foreign minister where he tried to secure Germany’s economic independence through the Dawes (1924) and Young plans (1929) which limited war reparations. Other politicians were either powerless or hankering for (a disastrous) war. His courage in an atmosphere of helplessness or belligerence is to be admired. It was Germany’s loss when he died suddenly in 1929. It is highly likely that he would have become President and blocked the rise of Hitler with his mix of patriotism and social reform.

Whilst he expressed some views at odds with NL ideology e.g. restoring the the monarchy and imperialism he was a product of his environment and the times.

He supported his nation and defended it when countries tried to rip Germany apart. He also promoted self-determination and fought to maintain liberty, independence and democracy (in a country more at ease with authoritarianism) through peaceful negotiations and constructive agreements. Overall he is a symbol of what one man can do if he has the ideas and the motivation to see those ideas through.

Date: September 23, 2010