THIS is the fourth in a five part series about Distributism. The original was written by Richard Howard in 2005 and appeared on the web-site – http://www.hsnsw.asn.au/index.php – of the Humanist Society of New South Wales..

As we have previously noted, Distributism (and partially Social Credit) remains one of the key influences relating to the social and economic ideals of National Liberalism. This is because National Liberalism rejects both capitalism and socialism and seeks to promote a third alternative that goes way beyond these two positions.

National Liberalism believes that capitalism and socialism are effectively different sides of the same coin. Both systems place the means of production into the hands of a minority at the expense of the masses. In capitalism, land and capital are controlled by a small number of powerful business people, while in socialism that same power was held by a small number of politicians. In these scenarios, the vast majority of citizens had little control over their own economic fortunes. National Liberalism, on the other hand, believes in economic and social self-determination and freedom.

We invite our readers to share their thoughts when this article is reproduced on our Facebook site https://www.facebook.com/groups/52739504313/ It goes without saying that there are no official links between Richard Howard, the Humanist Society of New South Wales and the National Liberal Party. Readers will note that this Introduction uses the phrase ‘third position’ and that the article uses the phrase ‘Third Way.’ Here they are used in a context that distinguishes it from capitalism and socialism – indeed, it refers to an economic position that goes way beyond both capitalism and socialism.

.

Distributism As A Means of Achieving Third Way Economics (Part 4)

“Under capitalism, man exploits man. Under communism, it’s the other way around.”

How Distributism Works

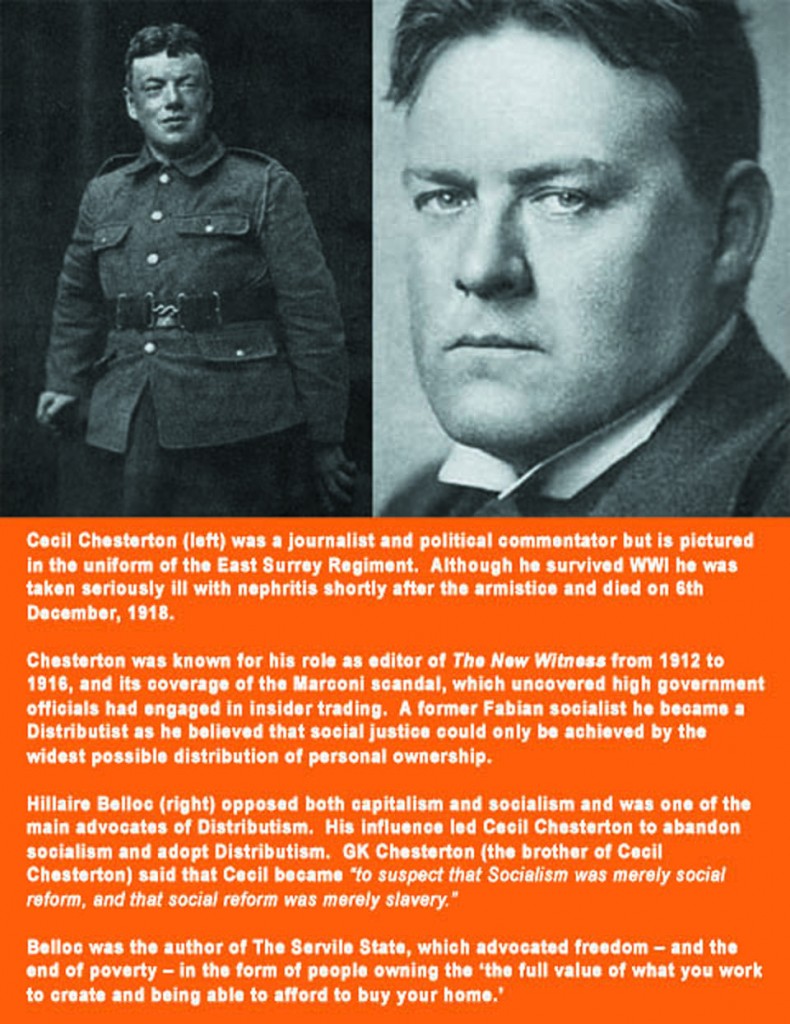

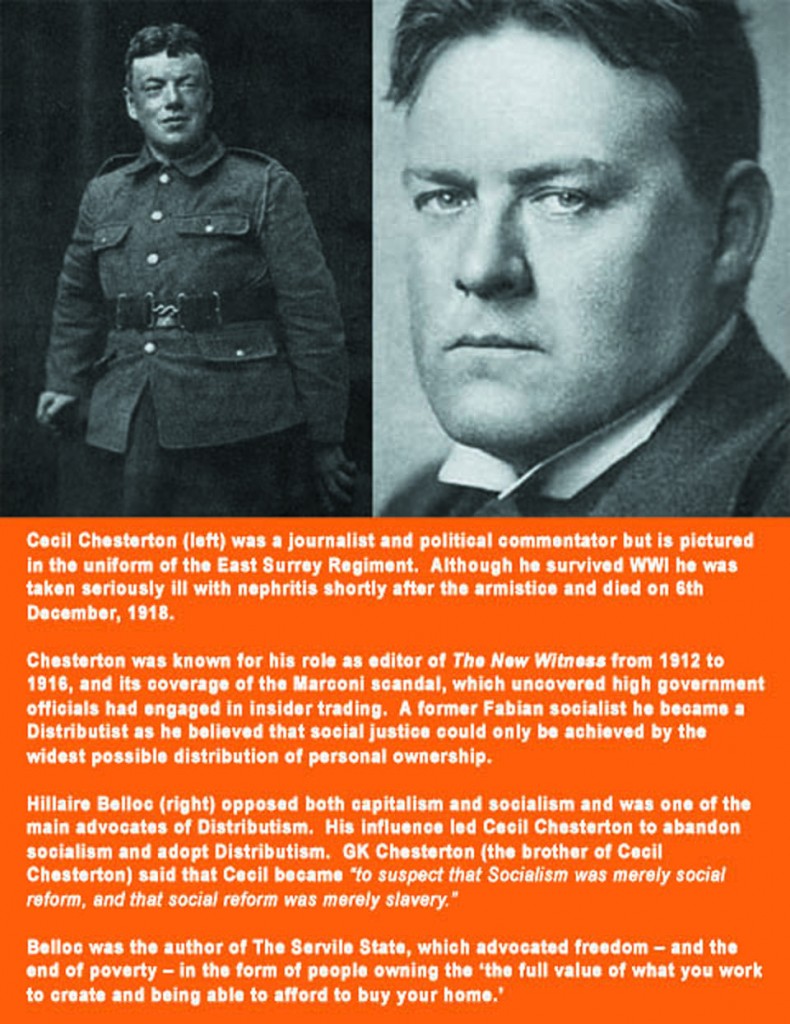

The key work to understanding early 20th century distributism is Belloc’s seminal work, the Servile State.

The key work to understanding early 20th century distributism is Belloc’s seminal work, the Servile State. A savage denunciation of laissez-faire capitalism, which Belloc argued was re-establishing feudal servility on economic lines, the Servile State is no less savage towards state socialism, which (ironically presaging the later words of free market economist Friedrich Hayek) Belloc called no less a road to serfdom.

Belloc argued that what a divided Britain with a vast impoverished underclass needed was not ever more unrestrained capitalism nor the false dawn of socialism, but a new liberalism, which for Belloc was first last and foremost about liberty.

Freedom, however, as Belloc well knew, isn’t free. What use is the mere absence of the physical control of others if your poverty renders you subject to their financial control? It’s simply a subtler form of tyranny.

The beginning of freedom is the end of poverty and the end of poverty argue the distributists comes not with state ownership or welfare handouts but with owning the full value of what you work to create and being able to afford to buy your home, not living by another’s leave.

Belloc was elected to parliament shortly before the First World War and served in the government of Lloyd George, but his uncompromising personality denied distributism the opportunity it could otherwise have gained.

For all its colourful leadership by Belloc and Chesterton, and the considerable publicity it enjoyed in the 20s and 30s, distributism was never implemented in Britain and after its dalliance with Oswald Mosley’s New Party, it never recovered public credibility when Moseley turned to fascism.

The laurel for outstanding success in implementing distributist aims must rest with the Spanish, where following the Spanish Civil war, Don Jose Maria Arizmendiarrieta founded the Mondragon Co-operative in the Basque region. From a handful of unemployed oil lamp makers, Mondragon has grown to become the ninth largest corporation in Spain.

Unlike the isolated and fragmentary co-operative experiments in Australia and Britain, Mondragon is an expression of the broad distributist agenda that seeks not simply to sell to its members at a discount but to transform their lives. To consistently improve living standards through sustainable development and to rebuild community and culture as opposed to promoting dog-eat-dog adversarial individualism.

Mondragon co-operative runs supermarkets, banks, agricultural and manufacturing concerns, housing projects, schools, technical colleges and even a university!

The lot of the poor is improved not through welfare but through economic empowerment.

Capital is seen not as the enemy but as an instrument for social progress.

The co-operative, in the Mondragon experiment is viewed as a means by which instead of capital hiring labour, labour can hire capital.

Some see the kind of distributism which Mondragon represents as an evolutionary development of socialism, in which the role of the state is abandoned in favour of locally controlled and owned production. Others, see the Mondragon experience as a new kind of democratic capitalism, in which the wealth-generating power of capitalism has been harnessed to achieve social ends.

In the end though, if capitalism is simply about maximizing profits and standing back even if that leads to monopoly ownership, then Mondragon isn’t capitalism. And if socialism is about collective ownership rather than private profit, Mondragon isn’t socialism either, because Mondragon is all about making individuals and their families wealthier.

To be continued.

The key work to understanding early 20th century distributism is Belloc’s seminal work, the Servile State.

The key work to understanding early 20th century distributism is Belloc’s seminal work, the Servile State.