Devon Voice Debate (1) – Universal Basic Income For Devon? (Part II)

AS NATIONAL LIBERALS we’re interested in looking at ideas which can probably be best described as being ‘Neither Left nor Right – Neither Capitalism nor Socialism.’ Indeed, we’re interested in ideas that go way beyond these positions.

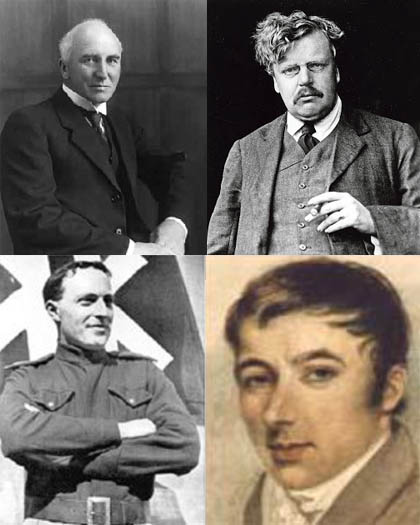

As ‘points of reference’ we look towards the original Liberal National Party/National Liberal Party, Distributists like GK Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc and monetary reform ideas – such as Social Credit. Although we’re not Socialists, we’re interested in folks like Kier Hardie and Bob Blatchford and Guild Socialists like William Morris, GDH Cole and Arthur Penty. The ideas of the Co-operative movement, Syndicalism, the Chartists and Levelers and support for small businesses and shopkeepers, and some libertarian economists, are also of interest.

With the above in mind, Devon Voice – The Voice Of The National Liberal Party In Devon – is reproducing an article by Brian Bergstein from MIT Technology Review – see the original here https://www.technologyreview.com/s/611418/basic-income-could-work-if-you-do-it-canada-style/ – which looks at the introduction of a trial system of Universal Basic Income in Lindsay, Ontario, Canada. The Universal Basic Income (UBI) is generally understood to be a guarantee from the government that each citizen receives a minimum income which is enough to cover the basic cost of living. The UBI is also designed to provide financial security – particularly in the not-to-distant future where it can offset job losses caused by technology.

Originally called Basic Income Could Work – If You Do It Canada-Style, Devon Voice is reproducing it in three parts. This is part two and it should be read directly on from part 1: http://nationalliberal.org/devon-voice-debate-1-–-universal-basic-income-for-devon-part-1 As always, debate is free with Devon Voice & the NLP. Therefore, we’d appreciate your views on this article (and the idea of Devon introducing the UBI) when it appears on either the National Liberals Facebook site – https://www.facebook.com/groups/52739504313/ – or the National Liberal Party Facebook site – https://www.facebook.com/NationalLiberalParty/ – It goes without saying that there are no official links between Brian Bergstein, MIT Technology Review, Devon Voice and the National Liberal Party. Please note that the NLTU has kept the original North American spelling and phrases as they are.

.

Basic Income Could Work – If You Do It Canada-Style (Part 2)

A Canadian province is giving people money with no strings attached – revealing both the appeal and the limitations of the idea.

Basic income as a social equalizer

‘Points of reference’ for Devon Voice - The Voice Of The National Liberal Party In Devon – include social and economic ideas advocated by the likes of Sir John Simon (top left), GK Chesterton (top right), John Hargrave (bottom left) and Robert Owen (bottom right). In an effort to protect British industry, Sir John Simon, the leader of the Liberal National Pary/National Liberal Party supported a form of protectionism. GK Chesterton was a well-known advocate of Distributism, which advocates the widespread ownership of both property and the means of production. John Hargrave was the leader of the Green Shirt Movement for Social Credit (aka The Green Shirts) which battled both Mosley’s British Union of Fascists and the Communist Party of Great Britain. Also, in opposing the power of the banks, Hargrave promoted economic reform. Robert Owen is best known for his efforts to improve the conditions of factory workers. He is regarded as one of the founders of the wider cooperative movement.

The Olde Gaol Museum is indeed an old jail, but it’s also a showcase for things that reveal the texture of Lindsay’s history—uniforms that nurses from town wore in France during World War I; tools and maps used by railway workers when this was a hub for eight railroad lines; 19th-century paintings by a local artist who depicted the timeless regional pastimes of canoeing and fishing. When curatorial assistant Ian McKechnie gives me a tour, he stops and plays a lovely tune on a foot-pumped organ called a harmonium that was made in Ontario more than a hundred years ago.

McKechnie, 27, has worked at the museum for seven years and is devoted to it. Unlike his previous job, when he was briefly a laborer at a goat cheese factory, it offers a chance to be creative and connect with many people in the community. He doesn’t just give tours: he researches and organizes exhibits and writes supporting materials. But on the day we meet, the museum is not paying him to be at work, and therein lies a story about why he and the Olde Gaol’s operations supervisor, Lisa Hart, both signed up for the basic income.

The museum gets almost all its revenue from grants, and one just expired. The manager of the museum recently left, and so it falls largely to McKechnie and Hart to keep things going until another grant comes in. Even when it does, these won’t be lucrative jobs—perhaps $20,000 a year for McKechnie’s. They could find positions in the area that pay more, but both would much rather continue their labor of love at the museum. Leaving now might undercut its momentum toward a more sustainable future, which could include a new cultural center that would connect the museum with a local art gallery.

Thanks to the basic-income trial, both can afford to stay on with the museum. And in the meantime, Hart says, she will no longer put off buying new eyeglasses. The basic income “allows you to spend time on something that’s valuable,” she says. “It’s very sad to walk away from something where you’re valued and doing something meaningful for the community because it just can’t pay you a lot.”

This highlights an intriguing aspect of basic income: it functions in different ways for different people. The way Hart describes it, it’s fuel for cultural development. For Dana Bowman, who might now take classes in social work and regularly volunteers at a community garden, it’s a food subsidy, an educational grant, and a neighborhood improvement fund all in one. For a married couple who own a health-food restaurant that barely covers its costs, it’s a small-business booster. A man who hurt his back working in a warehouse told me he hoped it could augment his employer’s disability payments. A student who was about to graduate from a technical college and had a job lined up said he planned to use the extra income to pay down school loans and start saving for a house.

For McKechnie, the basic income is something broader: a social equalizer, a recognition that people who make little or no money are often doing things that are socially valuable. “It gives one the assurance that the work you’re doing is not in vain, even though you’re not working in a bank or doing other things that are considered part of a career,” he says.

Even if a basic income turns out to be a flexible and efficient government program, it’s not clear that it would be a great way to respond to technological unemployment. Over and over again, people in Lindsay told me it won’t reduce people’s demand for jobs.

As a practical matter, the Ontario trial doesn’t pay enough to eliminate most people’s need to work or to rely on family for support. But even if a richer payout were feasible, that wouldn’t change the philosophy of the program. Basic-income supporters want to improve the odds that people will take better care of themselves and their families. They want a humane and dignifying way of helping people who simply can’t work. But they also argue that most people generally want and expect to work. “It’s not supposed to be welfare for people displaced by technology,” says one of the basic-income advocates, Mike Perry, who runs a medical practice in Kawartha Lakes.

Moreover, while giving poor people money helps them, it still leaves urgent and difficult questions unanswered about the impacts of automation and globalization. What will it take to ensure that entire regions aren’t left far behind economically? What can be done to boost the supply of good, steady jobs? Basic income “is only the beginning,” says Roderick Benns, former vice chair of the Ontario Basic Income Network. “It’s not just ‘cut a check and get on with building the corporatocracy.’ We have to ask what else we are doing as a society to get people to reimagine what they can do with their lives.”

Benns, the author of several books, grew up in Lindsay. Until recently, he and his wife, Joli Scheidler-Benns, lived three hours away, but the pilot is so important to them that they moved back so he can chronicle it in a new publication called the Lindsay Advocate and she can do research for her PhD on the subject at York University. After Benns describes how basic income should augment job training and other social programs, Scheidler-Benns, who is originally from Michigan, nods and then adds: “I don’t see how it could work in the US.”

Date: August 22, 2019

Categories: Articles